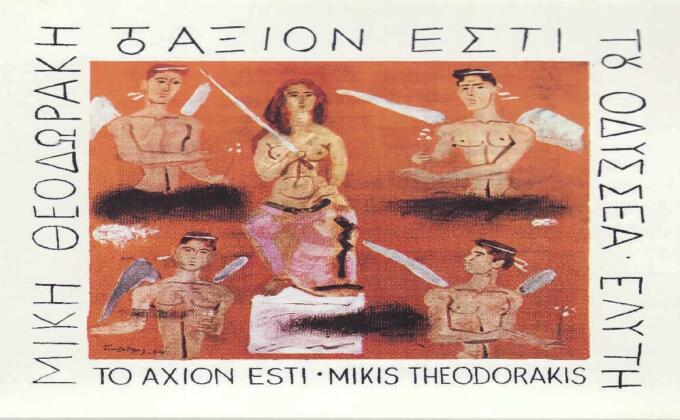

Nobel kesusastraan tahun 1979 membawa pembaca sastra untuk menyusuri laut Aegean melalui bait terkenal: ‘Drinking Corinthian sun, Reading the old marbles, Striding through vineyard seas, Aiming the harpoon At a votive fish that slips away’ karya pemenang Puisi Nobel, Odysseus Elytis. Sosok penyair ini, yang terkenal eskatis dan membatasi diri dari segala hiruk pikuk panggung kesusastraan, merupakan figur kunci dalam tonggak sastra Yunani modern bersama dua penyair pendahulunya, yaitu Kavafis dan George Seferis. Dalam ulasan (yang benar-benar) singkat kali ini, uraian tentang Elytis hanya akan mencakup pembahasan tentang Axion Esti, kumpulan puisi yang menghantarkan sang penyair meraih nobel–sedangkan kajian tentang aliran romantik dan geliat identitas modern Yunani dalam puisi Elytis akan dibahas lain waktu. Untuk memulai uraian, perlu rasanya memahami makna dari Axion Esti sendiri; secara etimologi, Axion Esti dapat diartikan ‘worthy it is; memang selayaknya’–frase yang kerap digunakan dalam himne Perawan Suci pada liturgi-liturgi klasik Bizantium atau pada sambutan Jumat Agung. Analogi religi ini kemudian digunakan Elytis untuk membangun alusi ‘kecantikan oppresif’ laut Aegean yang berkelindan ingatan masa lampau. Antologi ini lantas didapuk sebagai karya ‘paling ambisius’ dalam sastra Yunani modern–dan mungkin salah satu antologi paling kompleks bada abad dua puluh (Carson dan Saris, 1997)–sehingga wajar apabila perlu waktu tiga belas tahun bagi Elytis untuk merampungkan penulisan Axion Esti. Sebagai bentuk kontemplatif atas karyanya, Elytis memberikan sebuah penjelasan: “sudah waktunya bagi seseorang untuk melampaui periode klasiknya [sendiri], bukan dengan kembali ke batasan lama tetapi dengan penciptaan batasan baru untuk mencapai sebuah [de]konstruksi baru atas karya-karyanya sendiri” (dalam Pourgouris, 2016). Sebagai buah dekonstruksi batasan sang penyair, Axion Esti seakan berdiri sebagai sebuah karya dengan aturannya sendiri. Puisi ini digubah dalam tiga segmen, yaitu The Genesis (memaparkan tentang mimpi tentang awal utopia sebuah negara impian), The Passion (sebuah interaksi antara memori, fantasi dan kenyataan), dan The Gloria (upaya penyair untuk mewujudkan syair-syairnya menjadi sebuah bentuk realita). Atas dasar intensitas tersebut, akademi Nobel lantas memberikan penghargaan tertinggi kesusastraan pada tahun 1979 walaupun Axion Esti digubah oleh Elytis dua dekade sebelumnya, yaitu pada kisaran 1959. Di Yunani sendiri, popularitas Axion Esti sulit untuk ditandingi: digubah dalam bentuk lagu (pada tahun 1964 oleh Mikis Theodorakis), serta dijadikan slogan perlawanan terhadap junta militer Yunani di era 1970an. Namun, penghargaan Nobel yang diterima Elytis atas Axion Esti memberikan pengaruh signifikan, bukan hanya pada pengakuan atas karyanya, tapi bagi kesusastraan Yunani secara keseluruhan dengan dua poin pokok: (1) mengangkat kembali sastra Yunani yang kerap dianggap marginal dalam peta kesusastraan modern Eropa dengan menyandingkannya sebagai kejayaan kuno semata, dan (2) mengangkat kembali keberadaan penyair dalam narasi sejarah Yunani, yang selama rejim otoriter ditempatkan sebagai opssisi dan dilarang untuk bersuara (Pourgouris, 2016). Atas dasar pengaruh dan kekuatan alusinya, maka tidak ayal apabila Axion Esti merupakan kumpulan puisi yang mendefinisikan gaya kepenyairan Elytis sekaligus menempatkan sang penyair sejajar dengan para sastrawan modern seperti Rilke dan Eliot. Tanpa memperpanjang basa-basi, mari kita nikmati beberapa puisi dalam Axion Esti yang diterjemahkan ke dalam Bahasa Inggris oleh Carson dan Saris (1997).

Puisi Nobel Odysseus Elytis

The Genesis (Except)

IN THE BEGINNING the light And the first hour

when the lips still in clay

taste the things of the world

Green blood and bulbs golden in the earth

And the sea so exquisite in its sleep spread

unbleached gauzes of sky

beneath the carob trees and the tall standing palm trees

There alone

grievously weeping

I faced the world

My soul sought a Signalman and Herald

Then I remember I saw

the three Black Women

Lifting their arms to the East

Saw their gilded backs and on their right

the slowly dissolving cloud

that they left And plants of strange design

It was the whole many-rayed sun with its axle

in me that beckoned And

he who I truly was He many aeons ago

He still green in the fire He uncut from the sky

The Passion (The March to the Front)

AT DAWN on St John’s Day, the day after Epiphany, we received the order to move

up to the places where there are no weekdays or Sundays. We had to take over the

lines till then held by the army of Arta, from Heimarra to Tepeleni, because they had

been fighting without a break right from the start and only half of them were left and

they couldn’t hold out any more.We had already spent twelve days in the villages behind the lines. And as our ears

again became accustomed to the sweet rustlings of the earth, and timidly we gave

ear to the barking of the dogs, or to the sound of distant church bells, it was then we

had to return to the only din we knew: slow and heavy from the cannons, dry and

quick from the machine guns.Night after night, we marched without stopping, one behind the other, as if

blind. Slogging through the mud with great effort, we sank in up to the knee. Because

it often drizzled on the roads as in our souls. And the few times we stopped to

rest, we wouldn’t exchange a word, but grim and silent, with a little torch for light,

we shared out our raisins one by one. At other times, if we had the chance, we hurriedly

loosened our clothes and furiously scratched ourselves for a long time till we

bled. Because the lice had come up as far as our necks, which was even more unbearable

than our exhaustion. And then the whistle was heard through the darkness,

signaling us to start off again, and like pack animals we advanced as far as we could

before daybreak, when we would be targets for the airplanes. Because God had no

idea about such things as targets, and as was his wont, he always made daybreak at

the same hour.Then, hidden in gullies, we rested our heads on their heavy side, whence no

dreams emerge. And the birds got angry at us, thinking we paid no attention to their

words-or because we had perhaps made creation ugly for no reason. We were peasants

of another kind, with spades and iron tools of another kind in our hands, damn

them.Twelve days ago, while at the villages behind the lines, we had looked in the mirror

for many hours at the contours of our faces. And as our eyes again became accustomed

to their old familiar features, and we timidly gave eye to our naked lip or

our cheeks freshened by sleep, so we saw that on the second night we had changed

somewhat, on the third night even more so, on the fourth and last, it was obvious we

were no longer the same. It was as if, you might think, we were a motley crowd with

all generations and years mixed together, some from present times, and some from

times long past, whitened with an abundance of beard. Unsmiling chieftains with

turbans, and gigantic priests, sergeants from the wars of 1897 and 1912, axemen

swinging their axes over their shoulders, Byzantine borderguards, and shield-bearers

with the blood of Bulgarians and Turks still on them. All together, not speaking,

grunting side by side for innumerable years, we crossed ridges and ravines, thinking

of nothing else. Because as when continual setbacks always strike the same people

so they become used to Evil and finally change its name to Destiny or Fate-so we

advanced straight toward what we called Messed-up, as if we said Mist or Cloud.Slogging through the mud with great effort, we sank in up to the knee. Because it often

drizzled on the roads as in our souls.And we realized that we were very near the places where there are no weekdays

or Sundays, neither sick nor hale, neither poor nor rich. Because the distant boomings,

something like a thunderstorm behind the mountains, kept getting louder, so

much so that we could finally make them out, slow and heavy from the cannons, dry

and quick from the machine guns. And because, more and more frequently, we came

across medics with the wounded, moving slowly from the front. Wearing armbands

with red crosses, they set down their stretchers and spat in their palms, their eyes

wild for a cigarette. And when they heard where we were heading, they shook their

heads, and began to tell horrible stories. But the only thing we paid attention to were

those voices in the darkness, rising still burning from the pitch of the pit or from the

sulphur. “Oh mother, oh mother.” And sometimes, less often, we heard choking gurgles,

like snores, which those in the know said were the death rattle itself.

Sometimes the medics brought prisoners with them, captured only a few hours

before during the sudden attack by the patrols. Their breath smelled of wine and

their pockets were full of food tins and chocolate. We didn’t have such things, because

the bridges behind us were down, and our few mules were incapacitated by

snow and slippery mud.Finally, rising smoke appeared here and there, and the first bright red flares on

the horizon.

The Gloria (Excerpt)

Axion Esti the lantern’s passage

filled with ruins and black shadows

the page written under earth

the song Lithe-Girl sang in HadesThe carved-wood monsters on the icon-screen

ancient poplars sparkling like fish

lovely Korai with their stone arms

and Helen’s neck that’s like a beachTHE STARRY trees with their good will

musical notation of another world

the old faith that the very near

and yet invisible always existsThe shadow that leans them toward the earth

a something yellow in their memory

their ancient choral dance over the tombs

their wisdom that’s beyond all price

Interpretasi Musik (Mikis Theodorakis)

Sumber Gambar: Wikimedia commons

Sumber Bacaan:

Elytis, O. (Terj, J. Carson dan N. Sarris). 1997. Collected Poems of Odysseus Elytis. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Pourgouris, M. 2011. Mediterranean Modernisms: The Poetic Metaphysics of Odysseus Elytis. Ashgate Publishing Company.

kontak via editor@antimateri.com